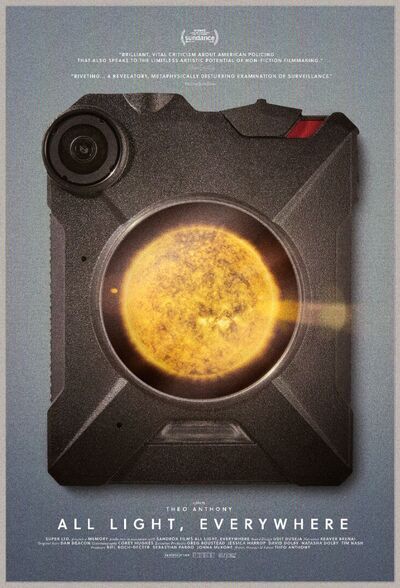

I am still a month behind with this. Nevertheless. Discussed in this post: 15 books (How to Change Your Mind; The New Way of the World; Never-Ending Nightmare; Family Values; On Violence and On Violence Against Women; Culture Warlords; Lectures on Russian Literature; Extinction; An Untouched House; Pastoralia; The Encyclopedia of the Dead; Dancing in Odessa; Letters in a Bruised Cosmos; Becoming Unbecoming; and They Called Us Enemy); 2 movies (Fugue; and Nosferatu the Vampyre); and 3 documentaries (Heimat is a Space in Time; Perfect Bid; and All Light, Everywhere).

BOOKS

1. How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence by Michael Pollan.

Sometimes, if you stumble upon an interesting topic like, oh, some of the long-neglected but actually super-exciting ways in which psychedelic plants interact with human consciousness, but you want to write more than an article for Vox or the Times, you can pad your material and produce something book-length by adding a bunch of personal narratives and history and stories about different people who were influenced this history. If you’re not sure how to to do this, and get away with it, I suggest reading Michael Pollan’s book. If, however, you want to learn more about psychedelics, I think the internet is your friend.

2. The New Way of the World: On Neoliberal Society by Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval.

First published in 2009, The New Way of the World provides a useful overview of the 20th century and explains how neoliberalism went from being a fringe perspective to being hegemonic. Especially useful is their explanation regarding the rebranding of both individuals and governments as entrepreneurs and the ways in which the “neoliberal subject” becomes self-governing and, in fact, finds their own hopes and dreams caught up within the neoliberal imaginary. A great resource.

3. Never-Ending Nightmare: The Neoliberal Assault on Democracy by Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval.

Following up on The New Way of the World, Never-Ending Nightmare was published in 2016 and looks at what happened to neoliberalism, and all of us, after the market crash of 2007-2010. Here, Dardot and Laval attend to the persistence of neoliberalism after the crisis because of its profoundly anti-democratic apparatuses, its ability to profit through crises, the ways in which it enslaves individuals, groups, and nations through debt, its linkage of oligarchies to the rule of law, and the ways in which neoliberal rationality drives out other ways of thinking. This is an excellent book and goes a long way to explaining why austerity rather than revolution came after 2008.

4. Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism by Melinda Cooper.

I grew up in the ‘80s and ‘90s when Christian Conservatives, including my own parents, and the so-called “Moral Majority” were harping on about “family values.” Later, I did extensive research into the ideology of early Roman imperialism and I was struck by the role played by “family values” within the moral reforms instituted by Augustus and his heirs. Family values, I concluded (and also demonstrate in my book, Pauline Eschatology: The Apocalyptic Rupture of Eternal Imperialism), are deeply implicated within and connected to imperialism. This is as true of ancient Rome as it is of America.

Some have argued that neoliberalism changes all of this. With its vast expansion of markets into all domains of life and its ubiquitous logic (and morality) driven by profit-making, neoliberalism is frequently said to dissolve more conservative moral codes. The marketing of queer culture(s) is a frequently cited example of this.

Melinda Cooper demonstrates that things are not as simple as all that. Observing that free-market neoliberals (from Hayek onwards) are often in cahoots with social conservatives she asks why this is the case. She then demonstrates that the neoliberal emphasis upon personal responsibility that has been used to gut social services and the welfare state, actually relies upon family members taking responsibility for each other and shouldering the cost of expenses that used to be covered by the State. The morality of kinship obligations replace social safety nets. It’s a brilliantly argued book and this brief review does not do it justice. Highly recommended reading.

5. On Violence and On Violence Against Women by Jacqueline Rose.

A fairly loosely connected series of essays—the themes of “violence” and “violence against women” are rather broad—Jacqueline Rose primarily explores these topics through an exploration of literature and an examination of events in South Africa after the dramatic failure that was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. She brings the perspective of a psychoanalyst to these matters and is well-attuned to the violence that lurks inside of all of us. But this doesn’t mean that we are all equally violent and so the violence of men against women and trans folx deserves special attention. After all, as Rose observes, “violence is a form of entitlement” which is able to persist because it is frequently normalized and made invisible. According to Rose, this “shiftiness” is “the chief means whereby entitlement boasts its invincibility and hides its true nature from itself.” However, unveiling violence does not necessarily produce the end of violence and Rose’s later chapters on the utter failure of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to produce a less violent and less racist South Africa are extremely compelling in this regard.

Sexuality, a havoc-creating force if ever there was one, is also a key element in the production of violence today “For psychoanalysis,” Rose writes, “sexuality is lawless or it is nothing”). And repressing violent elements of our sexuality, something that Rose thinks lurks within everyone, only adds to this. Instead, she argues, we must take time to think well about violence, including “the equivocations of our inner lives” (not just our “conscious fantasies” but also our “unconscious fantasies” which are related to “something that would horrify you if it came to pass in real life”) if we want to put an end to violence. What Rose wants is an end to the viciousness of sexual violence and harassment, but an end that leaves open the question of “what sexuality, at its wildest – most harmful and most exhilarating, sometimes both together – might be”. I think the conclusion of Jane Ward’s book, The Tragedy of Heterosexuality (reviewed here) actually begins to point the way towards how we can arrive at that point.

6. Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacy by Talia Lavin.

Talia Lavin went undercover to infiltrate various virtual environments (and one or two in-person environment) where misogynistic White supremacists congregate. She does this, not so much to try and understand them, but in order to understand how these people can be better resisted and defeated. Proximity to some people does not breed sympathy (despite soft-ball pieces published about White supremacist in mainstream media outlets). And even the most cultured, sensitive, and educated Liberal may find themselves confronted with a rising feeling of hatred. Indeed, Lavin says, it is her proximity to these people—people who regularly call for genocide, who celebrate mass murder, who revel in the most violent imaginable rape fantasies—that taught her to hate. It’s a sad day for all of us idealists when we come to realize that, yes, sometimes hatred is called for. And those who are not in the trenches may never understand this. But, for all his flaws and as much as it makes my kindhearted, bougie Liberal friends cringe, Che Guevara got this right: “a people without hatred cannot vanquish a brutal enemy.”

7. Lectures on Russian Literature by Vladimir Nabokov.

Nabokov is a curious fellow. Unabashedly elitist, he is a proud and contemptuous aesthete allergic to any kind of moralizing or pontification in literature. Somewhat paradoxically, this makes him something of an anti-morals evangelist. But, oh no, the Nabokovian may object, the issue for Nabokov is less the moralizing as the ways in which lesser writers—writers like Dostoyevsky first and foremost—try to speak truth or share ideas, when literature proper present a certain image to the reader. Hence, for Nabokov, the description of a bug climbing upon a blade of grass brings more to a story than, say, two characters debating about the goodness of god (thus, for Nabokov, Tolstoy writes both the very best Russian literature and some of the most disappointing Russian literature depending on if Tolstoy is describing nature or lecturing his reader about this or that Christian value). For Nabokov, the great writer is a solitary man [sic] of genius, whose imagery produces a particularly powerful affect in the reader. As Svetlana Boym has shown, perhaps the affect Nabokov most appreciates is that of nostalgia. And, this points to another curiosity about Nabokov—the way in which he speaks with authority about the true or real Russia, despite having left Russia when he was 20 in 1919 and never once returning before his death in 1977. In this regard, he strikes me as a very American Russian and, for that reason, I wonder if another reader—George Sanders—may not be a better reader of the Russians than Nabokov himself is.

8. Extinction by Thomas Bernhard.

Thomas Bernhard is considered one of the greats of German literature (Austrian German in this case). In Extinction he presents us with a post-WWII aristocratic Austrian expat, thoroughly disgusted with his family’s and his nation’s Nazi-loving past (and present!), who is forced to reckon with these things when he receives the news that his parents and brother have unexpectedly died in a car accident. It’s a complex and carefully woven story. Bernhard’s reputation is well-deserved. This is a very personal work to Bernhard (who opted for physician-assisted suicide at the age of 58 and who then tried to prevent any of his work being available in Austria). What does one do with this kind of legacy? What can one do with it? The protagonist of the novel does his best… and it ain’t much. And that’s the situation we are all in.

9. An Untouched House by Willem Frederik Hermans.

I’ve only just started feeling out Dutch literature. My old man was born in Amsterdam and my grandfather on my mom’s side was a part of the Canadian troops that liberated Holland during WWII but, a few years ago, I realized I knew next to nothing about Dutch lit. So, I’ve been slowly feeling my way into it. A lot of it feels fairly dark. I’m not sure the Dutch really recovered from the complex traumas of the war—mass starvation, occupation, resistance, accommodation, betrayals, survival—and I wonder how much this relates to the resurgence of more extreme Right-wing politics in the Netherlands in response to neoliberal austerity in recent years (eg: Geert Wilders and the Party For Freedom).

An Untouched House is a story of one person’s survival within the resistance. But, here, there is nothing particularly heroic about being in the resistance. The hell of war extends into the subjectivity of even the most romanticized parties of our past. Survival is dirty. Victory is tainted. People are untrustworthy. Mostly, war produces devastation on all sides. My grandfather felt this way. It’s why he never participated in any kind of Remebrance Day ceremony that treated “our boys” as heroes and the enemies as monster. My grandfather saw a lot of “our boys” do truly horrendous things and, being stationed in Germany for some time after the war ended, also came to understand that many Germans were good people and that the line between “us” and “them” did not really apply. Hermans book vividly illustrates this not in relation to the troops but in relation to the supposedly more noble partisans. In this regard, I think the “untouched house” of the title, which is also a house that plays a prominent role in the book, can be said to be represent the Netherlands and the Dutch resistance. Not much is left of the house by the end. And that’s the point, I think. Recommended but not easy reading.

10. Pastoralia by George Saunders.

It’s no secret that I’ve become a bit obsessive about reading George Saunders. I’m fascinated by his mastery of his craft. Reading Saunders is an entirely pleasurable experience that makes me both a better reader and a better writer! What’s not to like about that? Pastoralia is an early collection of his short stories. Good times. Even though I’m not a huge fan of historical fiction, especially American historical fiction, I’m sorely tempted to pick up Lincoln in the Bardo to see how Saunders does with a full-length novel.

11. The Encyclopedia of the Dead by Danilo Kiš.

Kiš blends surrealism with a contemporary take on folk and fairy tales, and fits with my current fascination with literature out of central Europe, and so he seemed like a good fit for me. However, I found his voice to be rather dry… almost scriptural… and if the scriptures teach us one thing it’s that, dang, some really curious stories can be told in some really boring ways.

12. Dancing in Odessa by Ilya Kaminsky.

I really like Deaf Republic, Ilya Kaminsky’s award-winning poetry collection about soldiers in an occupied land who murder a deaf boy. So, I went back and picked up his debut work, Dancing in Odessa. It’s… good… but it didn’t rock my socks like Deaf Republic did.

13. Letters in a Bruised Cosmos by Liz Howard.

Indigenous star-knowledge, the images they see in the constellations, the stories they tell with the stars, and the ways in which they map meaning onto the cosmos, is something that has fascinated me for some years now. So, coming across any Indigenous poet who taps into some of this while also bringing in knowledge from Occidental astrophysics felt very exciting to me. But, you know, poetry is a fickle thing, especially if one desires a poet who produces a certain kind of affect in them rather than, say, reading poetry in order to appreciate the technical prowess and expertise of the poet. And so, as a result, I was somewhat disappointed with this collection.

14. Becoming Unbecoming by Una.

The pseudonymous author of Becoming Unbecoming tells the true story of coming of age in Northern England in the 1970s when a serial killer was actively killing sex workers and girls. From the actions of the serial killer, to the (in)action of the police, to the ways in which she herself was “slut-shamed” during her formative years, this is an intimate and thoughtful reflection on what it means to grow up within an environment where sexual violence against women and girls is ubiquitous and only considered deviant in the most extreme circumstances (which, even then, are only explored halfheartedly or ineptly). Una is a creative story-teller and you can tell that years of work went into this project. Recommended reading.

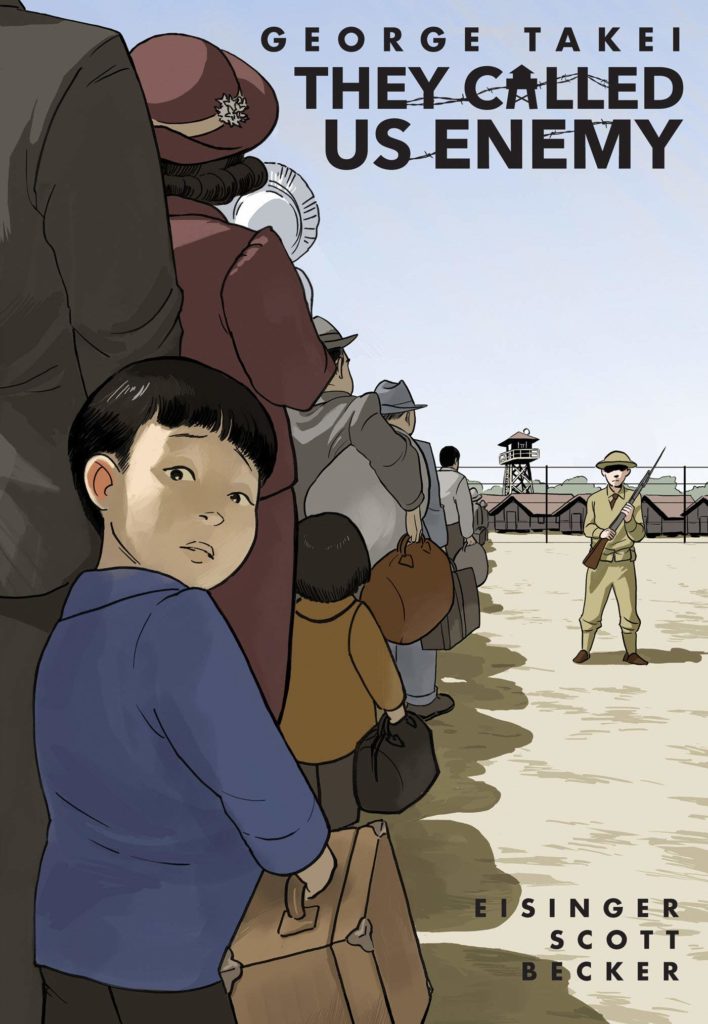

15. They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, Justin Eisenger, and Steven Scott. Art by Harmony Becker.

When he was a child, George Takei and his family were thrown into the system of concentration camps the American government created for Japanese-Americans during WWII. This graphic novel, relates Takei’s experiences there. It’s very well-done and, to me, is further proof that the genre of the graphic novel is especially well-suited for personal narratives and memoirs. Furthermore, this is an important but all-too-neglected element of American history and White supremacy. Recommended reading.

MOVIES

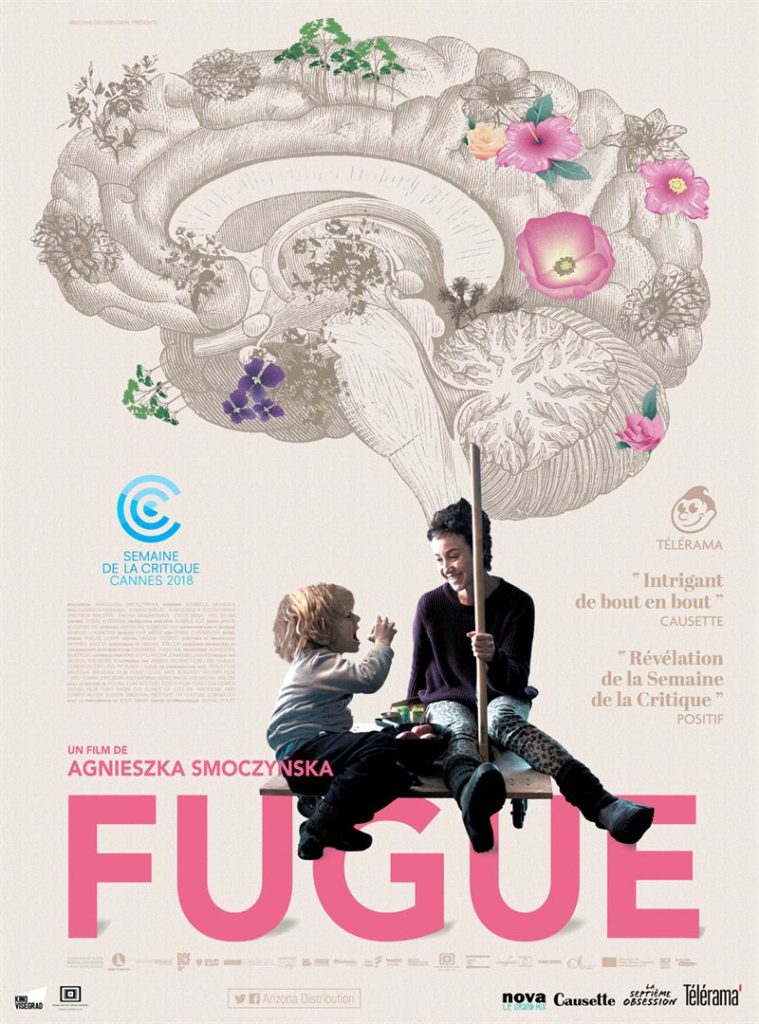

1. Fugue (2018) directed by Agnieszka Smoczyńska.

After watching The Lure, a horror musical about killer mermaids, I knew that I would watch anything else Agnieszka Smoczyńska chose to make. Fugue is an interesting follow-up to such a maniacally brilliant debut. It continues to exhibit her mastery of her trade but, after a strong opening scene (with a woman walking out of subway tunnel and then squatting and peeing on the platform in front of a public that looks on in horror and disbelief), it ends up feeling subdued and the final reveal feels, I hate to say it, contrived. The acting is strong, the framing is great, the tone and colour and directing is all top-notch but the story, dang, the story falls flat. I’ll wait and see where Smoczyńska goes next.

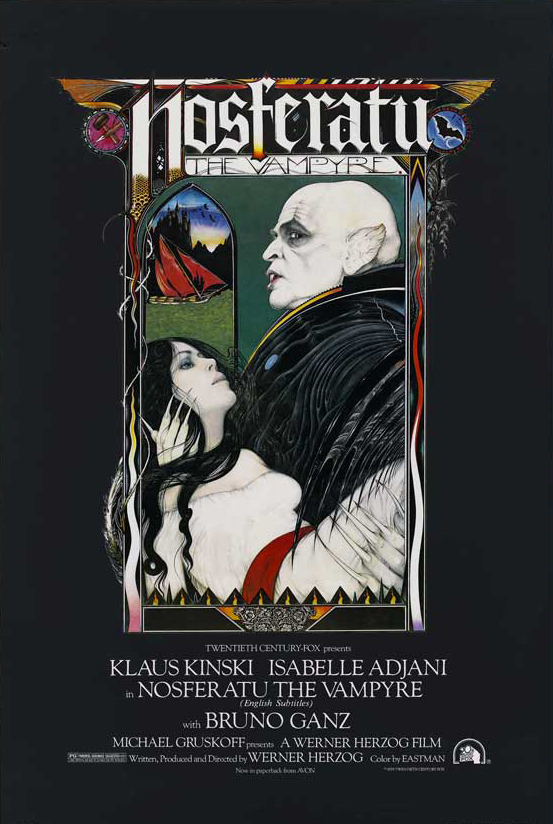

2. Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) directed by Werner Herzog.

Nosferatu the Vampyre is Werner Herzog’s reinterpretation of Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s definitive vampire film, Nosferatu (1922), and it stars Herzog’s early muse, Klaus Kinski. Known for his violent rage, it was later revealed that Kinski physically and sexually abused his daughters over a period of several years; leading me to wonder who all knew about this abuse but didn’t say or do anything about it—did Herzog?—after all, Kinski spoke openly about thinking it was absurd that German men could not legally have sex with twelve-year-old girls while people in other cultures got married at ages younger than that. Looking back on the film now, however, what stands out to me is neither Kinski’s highly-praised portrayal of Count Dracula, nor Isabelle Adjani’s ethereal take on Lucy, nor even Roland Topor’s giggling madman, Renfield (although Topor does come close to stealing the show). Instead, what ends up feeling timeless are the sets and scenery Herzog selects—from Carpathian mountains, to Czech and German castles, to Dutch canals, to masses of rats in a townsquare, it is almost as if the environment—both “constructed” and “natural”—is the character that best stands the test of time. More than creepy-crawling fingers, gasping innocents, rolling eyes, and high-pitched giggles, it’s the world in which the film occurs that most draws in the viewer. This, I think, speaks to Herzog’s talent as a director and makes the movie not only a classic campy movie, but a classic film. The scene where people dance and feast in a town square littered with coffins and plagued by rats, because they know today they live and tomorrow they die, is absolutely remarkable. It reminded me of the sudden and unlooked for breathlessness produced by the zero gravity scene in Solaris or the opening montage in Antichrist. It is scenes like this one, or the scene where Bruno Ganz (as Jonathan Harker) trudges towards the cloud-shrouded crags of the Transylvanian mountains that truly make this film.

DOCUMENTARIES

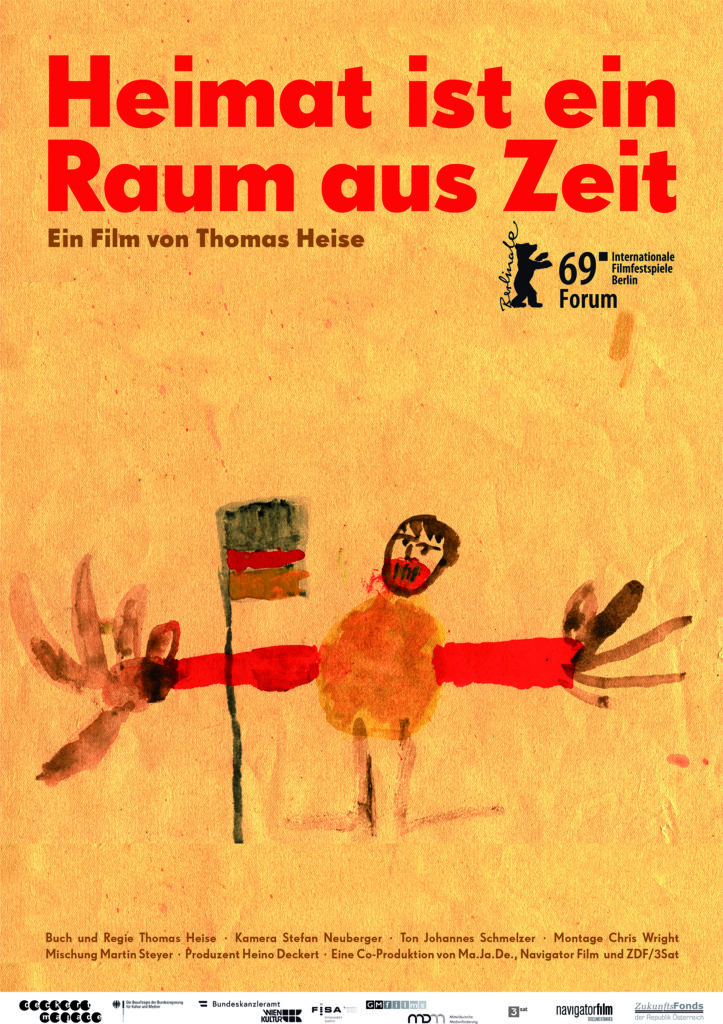

1. Heimat is a Space in Time (2019) directed by Thomas Heise.

I have been thinking a lot about how Germans, after WWII, have reckoned with what they and their loved ones did, how they have dealt with things like collective guilt (see, for example, Karl Jaspers, The Question of German Guilt) or what it means to desire to have some kind of homeland when the very idea of a homeland was central to the genocidal actions of the Nazis (see, for example, Nora Krug’s excellent graphic novel, Belonging). So, when I came across Thomas Heise’s 3.5hr long documentary exploration of this theme (as it relates to four generations of his family), I was eager to check it out. It’s a challenging documentary to watch because Heise isn’t all that concerned with making a movie that, say entertains the viewer. Instead, the narrator drones one in a monotone for (literally) hours, making various comments, reading various correspondences, and leaving it to the viewer to tie the threads together. In the meantime, one watches as various black and white shots (a non-descript field, a non-descript building, a non-descript row of trees, a non-descript pile of dirt—all generic scenes that look like I could have gone out with a video camera and filmed a few blocks from my home) slowly pass in front of the camera. What makes this challenging is not entirely the dullness of the presentation—in fact, that very dullness raises excellent questions: should documentaries that struggle with themes like genocide and guilt be entertaining? what does it say about us as viewers if we struggle to remain engaged with those themes if they are not presented in an entertaining manner?—as the fact that it is sometimes difficult to see how the weaving of the information can take place. This feels kind of like a personal data dump, with some connections made, but no immediate point to any or all of it other than, perhaps, the way that the director obviously struggles with the material. And perhaps that’s the point. Maybe we are supposed to only end up feeling conflicted. Maybe the viewer is also supposed to be left with a struggle that, far from ending, actually goes on and on and on.

2. Perfect Bid: The Contestant Who Knew Too Much (2017) directed by C. J. Wallis.

An amusing story about a mathematician who became obsessed with “The Price is Right” and who ended up being able to perfectly predict the price of items (including telling a contestant the exact price of a final showcase), I feel like Wallis kind of draws things out and grasps at material to make this a full length film. It would have been much better if it was much shorter.

3. All Light, Everywhere (2021) directed by Theo Anthony.

What do we want captured by the body cameras worn by police officers? Well, the spokesperson of Axon Enterprises explains, what we want is not something that actually shows the “objective reality” of the scene. Instead, we want to see what the police officer claims to have seen. Thus, for example, if a police officer sees someone lurking in the shadows who appears to be armed, we don’t want a camera equipped with night vision revealing to us that the person was actually just reaching for their wallet or carrying a lighter. Positioned on the officer and facing outwards—and with an easy on/off switch that officers can use to determine when to film—the body camera of a police officer should make jury members see things from the perspective of the officer and it should incline those same jury members to think and feel what the police officer states they thought and felt.

To me, this is one of the most important revelations in Theo Anthony’s somewhat sprawling exploring of film-making, image-framing, editing, and surveillance. At times, the sprawl seems to exceed Anthony’s grasp on the material, as though he is emulating Patricio Guzmán’s Nostalgia for the Light (is the similarity between the titles merely coincidental?) but is still finding his way into this craft. Nonetheless, I enjoyed the film very much and look forward to what Anthony does next.