Briefly discussed in this post: 18 books (Object-Oriented Ontology; Winnicott; Children of the Self-Absorbed; A Minor Chorus; The Tangled Tree; World of Wonders; The Face of War; A Visit from the Goon Squad; Speedboat; Homesickness; Scarborough; I’m Glad My Mom Died; Ducks; Trickster Feminism; The Translator of Desire; Pomba Gira and the Quimbanda of Mbùmba Nzila; Queen of the Seven Crossroads; and Maria de Padilla); 7 movies (White Noise; The Nanny; The Wrath of Becky; Sorry We Missed You; The House; Medusa; and Sobibor); and 2 documentaries (Bama Rush; and Running with Speed).

Books

1. Harman, Graham. Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything (2018).

Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) already feels somewhat passé, although Harman, its lead proponent, insists on calling it new in 2018 (almost twenty years after he first spoke of “object-oriented philosophy”). And that’s kind of the thing about ontology—which tries to distinguish itself from the baggage associated with metaphysics—it’s mostly clever kids playing in a sandbox of ideas and constructing all kinds of fun things, none of which are entirely convincing and none of which do not require an initial leap of faith to get on board with them. In many ways, the history of Western metaphysics, especially after Kant, is the application of Zeno’s paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise, only applied to the question of our ability to approach, access, relate to, describe, experience, or conceptualize what is real.

That said, what I appreciate most about OOO where it situates objects (which can be anything from a person to a rock to a webpage to an ecosystem to any kind of noun [person, place, or thing—wherein events, like the American Civil War, are also understand as things]). According to Harman, objects are simultaneously more than the sum of their parts (i.e., you cannot break an object down into its smallest components parts—like saying a human is just x percent carbon, x percent hydrogen, x percent phosphorus, etc., and then thinking you have now thoroughly described what a human is) and less than the sum total of its actions whereby it interacts with and effects other things (as if a human is only what they do or how other things know and experience them). Of course, various schools of thought have argued for both of those alternatives but Harman and OOO doing a decent job of criticizing both those alternatives (and, despite my using humans as examples, they also do a great job of bringing non-human objects into focus in a “flat ontology” that rejects initially importing any kind of hierarchical taxonomy into our understanding of being). So, okay, I think there is an important point here in terms of the being of things, one that at least resonates with me, but as with any ontological meandering, the criticisms of other ontologies are always easier to accept than the proposed solutions (unless one first makes one or more leaps of faith). In fact, I found a number of Harman’s points unconvincing and actually somewhat troubling. And I’m not alone here. Which is why, although Harman intends to write an accessible summary of OOO so that more people will pick it up and run with it, this book actually feels more like an extended dictionary entry on just one more fun way to fantasize about being that had a moment in the sun in the first dozen years of the twenty-first century.

2. Phillips, Adam. Winnicott (1988).

When the student surpass the master, it is well-worth reading what the student has to say about the master. In situations like this, the commentary is really better than the primary source and this is precisely what the reader finds in Adam Phillips short summary engagement with D. W. Winnicott’s life and work. Phillips is one of a few psychoanalysts writing from out of the British tradition for a popular audience whose work has been very influential on me (the other two are Darian Leader and Christopher Bollas), and he writes with his usual clarity, thoughtfulness, and creativity (all things that Winnicott, himself, appreciated!). If you’re looking for a book that gives you quick and easy access to one of the most influential thinkers in the British psychoanalytic traditions (and in psychoanalysis more generally), this is a good place to start.

3. Brown, Nina W. Children of the Self-Absorbed: A Grownup’s Guide to Getting Over Narcissistic Parents (2001).

I spent much of the first part of adulthood sorting how the harm, trauma, and abuse I had received from my father, mapping out the ways it had affected me, uprooting behaviour that arose—not as mirrors of his behaviour but as unhealthy responses to his behaviour—and finding my way to self-confidence and joy in living, instead of walking around feeling like a piece of shit and wanting to die all the time. However, over the last few years, it has become increasingly clear to me that I have neglected considering the hurt inflicted upon me by my mother because I was self-soothing by clinging to a fanstasy that, although my dad was a terrible dad, my mom was a good mom. The truth that I finally realized, is that neither of my parents were good parents. Both were entirely self-absorbed and destructive narcissists (my dad in a way that was intent on violently destroying his children, my mom in a way that tried to violently absorb her children into herself). Reading through Bowlby and Winnicott, and those who have followed after them, has given me much to think about in this regard.

As a result, I thought it might be useful for me to engage in more practical, workbook on this topic. Nina Brown’s book was a good choice for me. Undoubtedly, working through such things is difficult, but I’m glad I put in the work and took the time I needed to go through this text and its various exercises. I have been focusing lately on being more solid in-as-and-for-myself and, it turns out, that is precisely the kind of work Brown focuses on doing with adults who are the children of self-absorbed parents. Recommended to those for whom this is relevant.

4. Belcourt, Billy-Ray. A Minor Chorus (2022).

I have greatly enjoyed the poetry of Billy-Ray Belcourt (especially This Wound is a World) but I didn’t jive as much with his more recent narrative-based autotheory stuff. So, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to read A Minor Chorus when I first picked it up but, wow, I am glad that I did. I think he is really finding his voice as a fiction author (i.e. this is not quite autotheory although that isn’t far away) and it’s exciting to witness and to read. In A Minor Chorus the narrator is a Queer Indigenous person who moves from a remote reserve to the urban Academy and then who returns to the reserve with new questions and different perspectives. It explores grief, loss, sexuality, subversion, resistance, collective and individual identities, indigeneity and settler colonialism in carefully-crafted, understated, and therefore all the more affective ways. Recommended reading.

5. Quammen, David. The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life (2018).

Evolution is a complicated thing. For a lot of reasons. And, as David Quammen emphasizes in this book, modeling evolution as a tree (with a trunk and then large branches and then smaller branches and then twigs and so on) is not only overly simplistic—it’s entirely false. This is especially true when engaging with bacteria and archaea, single-celled organisms who are constantly sharing DNA and RNA with one another and with their environment, but it is also true of larger organisms like us given that we, ourselves, are porous ecosystems composed of whole communities of other smaller organisms. Heck, even ~8% of our own human DNA—the thing we think is most definitive of us as homo sapiens sapiens—comes to us from viruses that entered into us, became part of us, and fundamentally changed our genotype and our phenotype (for example, viral DNA is why mammals have placentas… i.e., fundamental to why mammals even exist as mammals). So, in a model of evolution, all kinds of branches are merging together and splitting apart, moving towards complexification and then moving back towards simplification, combining together to create an entirely new thing (from prokaryotes to eukaryotes, for example), and then diversifying. Evolution is weird and awesome like that. This also begs the question of where evolution actually takes places (at a cellular level? at an organism level? at a population level?), which has been the subject of some debate (see, for example, Samir Okasha’s fairly technical book, Evolution and the Levels of Selection), although Quammen doesn’t get into that here. What Quammen gives us is a decent popular-level science book that updates the reader on what we talk about when we talk about evolution and that helps take down simplistic (but false) views that were popularized by earlier models of evolutionary science. Like much popular science, I found it to be heavy on the bio of scientists (especially heavy, actually), and felt it could be benefited from more science. I also didn’t feel like Quammen wasn’t adding too much to what has already been published in this area, even at a popular level, although, of course, he does add a bit. All in all, a decent book and a good reminder of some things that are better explored elsewhere.

6. Nezhukumatathil, Aimee. World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments (2020).

In a series of twenty biographical meditations more or less loosely structured around a focus on a specific animal, Aimee Nezhukumatathil presents the reader with a tender, thoughtful, playful and moving collection. The prose is simple and short but the thoughts the book provokes linger for awhile. It reminded me of a more stripped-down version of Sabrina Imbler’s How Far the Life Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures (although, checking the publication date on that, I see that Nezhukumatathil’s book was published first). I find books like these enjoyable although not quite at the same level as those who are doing the best works of autotheory, documentary fiction, or meditations on the world around us, within us, and beyond us.

7. Gellhorn, Martha. The Face of War (1988).

In Marcel Ophul’s documentary about war journalism (The Troubles We’ve Seen [1994]), he interview Martha Gellhorn (notorious for sneaking onto a hospital boat so she could be present at the D-Day Invasion and for then having her report of that event stolen by her then-partner and all-around dickhead, Ernest Hemingway). Gellhorn and Ophuls have the following exchange:

Gellhorn: “The brave are funny. I’ve observed this in war. All the bravest men, all the bravest people—they’re funny. They are not self-glorifying. They are not solemn. They are jokers. And you can almost tell a brave man, woan, or child—”

Ophuls: “—from their sense of humour.”

Gellhorn: “Yes.”

I knew then that I wanted to read Martha Gellhorn’s work. The Face of War is a small collection of articles she wrote on various wars and militarized conflicts that took place in the mid-to-late twentieth century (the anti-fascist war in Spain, the Second World War [from Norway to Germany to Italy to China], the post-colonial war in Indonesia, the Six Day War in Palestine, the Vietnam War, and the dictatorial wars against the people sponsored by the USA in El Salvador and Nicaragua). She also provides some later reflections on each of those wars and, to a certain extent, retroactively critically engages her own work. Gellhorn is at her very best when discussing World War Two and criticizing her own government (i.e. the American government) for the wars they fought and encourage after WWII. Her anti-fascism, her astute insights, the perspective she has developed from being engaged on-the-ground, and her dedication all contribute a lot to what she has to say. She is, however, at her weakest when talking about post-colonial struggles for liberation (including Palestinian struggles) and here one sees some of the tropes of the greatness of White European civilization, excuses or denial of colonial violence, and generalized racism towards BIPOC communities surfacing. It’s an interesting study of how someone can both rebel against their own context and get some things very right, and also still be deeply enmeshed in their own context and get some things very wrong. Nonetheless, I very much enjoyed reading this book.

8. Egan, Jennifer. A Visit from the Goon Squad (2011).

There are various streams within American literature focused upon Americana and, I think, Jennifer Egan fits into the Phillip Roth, John Updike, Jonathan Franzen stream. These are authors who understand the structure of the classic novel, the techniques of showing and not telling, and the ways to develop characters that are relatable but also worth reading about, and who then go on to tweak the traditional ways of doing a story—but not overly much. This is good, solid literature in the tradition of good, solid literature. And if you have read a lot of good, solid literature you will read A Visit from the Goon Squad and think, yep, that was one of those books. But, also, if you have read a lot of good, solid literature, you might also be wanting to read something a little different. Which is where I found myself with this book.

9. Adler, Renata. Speedboat (2013 [1971]).

Some years ago, when I was still enamoured enough with the technical prowess of DFW that I overlooked (and simply did not bother learning about) what an absolute dick he was, I learned that he had a list of American literature he recommended his students read for his “Selected Obscure/Eclectic Fiction” course. As much as I have left DFW behind, the fact remains that working through that list introduced me to a number of excellent books I would not have read otherwise (The Man Who Loved Children by Christina Stead and Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin being the two biggest stand-outs). Speedboat was the last truly obscure (to me) book on that list so I was happy to find a copy and read it. Initially, I loved the book. Clever, humourous, affective, playfully non-linear and episodic, the talent here is obvious. However, the further I got into it, the more it smelled like upperclass White feminism (upon looking up Adler’s bio, it came as no surprise that she was a writer for both The New Yorker and The New York Times). Yes, she marvelously criticizes her own class, but she also does not hold back on racist, sanist, and classist criticisms of Others. Mostly she keeps those parts in check, but they bubble up at times and percolate around the periphery of the text and it’s really too bad because, damn, the writing is good (and, damn, it makes sense why DFW would admire this book).

10. Barrett, Colin. Homesickness: Stories (2022).

Over the last few years, I have become enamoured with short stories. When I was young, I gravitated towards the absurdly long works of literature (Tolstoy, Melville, Sienkiewicz, Musil, Proust, and more contemporary authors like DFW, Karl Ove Knausgaard, and Elena Ferrante—the longer the story, the more I wanted to read it), but then Borges, Ray Carver, and George Saunders converted me and convinced me that short stories are a genre all-their-own that is absolutely worth reading. Along the way, Kristen Roupenian, Carmen Maria Machado, Clarice Lispector, Richard van Camp, László Krasznahorkai, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, and even Roald Dahl and H. P. Lovecraft have made me grateful that I opened myself to short stories. It really is an entirely different kind of writing than what takes places in longer novels. Being new to the genre, I’ll still sorting out who is who and what is what and so I’m testing out different authors based on reviews they are getting from the critics. Homesickness is a collection I picked up because it was highly praised. I found it to be… okay. Set in Ireland (with the exception of one story that features a few Irishmen in Canada), the stories ebb and flow like the tide on a windless day. They carry a certain ennui that, I think, many people can identify with in the world of quiet devastation, existential lostness, and creeping impoverishment that has come to define the lives of people in the heartlands of neoliberalism. Everything is understated. The moments of climax are small, what denouements there are, are mundane. Which is kind of the point, I think. In my opinion, a decent collection but not exactly what draws me to this genre.

11. Hernandez, Catherine. Scarborough (2017).

Unexpectedly and deeply moving, Catherine Hernandez’s novel reminded me of so many loved ones I have known over the years. Writing about impoverished children, their parents, and the support worker who engages with them through a community-based program (whose funding structures and exploitative hierarchy the worker must navigate on her own), is a fraught terrain. Hernandez moves through it expertly. She honours the people of whom she writes but does not create caricatures or mere case studies. She exhibits some of the gritty realities of gendered and racialized poverty without dishonouring the people of whom she writes, and she writes what is oh-so-obviously a deeply personal love story in a way that has universal appeal and never falls into cheap romanticization. I am quite sensitive about these things—Hernandez writes about people who are very much like many of the people I have known and loved and who have also known and loved me over—and, instead of feeling any kind of negative way about her representations, what I actually feel is grateful. Thank you for writing this book and sharing it with us, Hernandez.

12. McCurdy, Jennette. I’m Glad My Mom Died (2022).

Jennette McCurdy was a child star, famous for a role she played on two Nickelodeon shows (shows I remember watching with my kiddos when they were much younger). However, McCurdy was shoved into this role by her narcissistic and, as we learn in this book, horrendously abusive mother. Child abuse takes many forms and a parent who refuses to allow a child to develop into their own self but who, instead, absorbs that child into the parent-self, is engaging in a truly insidious form of abuse that has long-lasting impacts on a person. All of that is captured in McCurdy’s memoir which, at times, almost feels like trauma porn which, I reckon, people especially love to read about people like former child stars.

McCurdy, however, is sensitive to these dynamics—she’s likely more in tune than most people as to the various ways in which people get exploited—and she writes because this is her story to tell, because she takes joy in writing and doing what she actually wants to do (instead of doing what her mother and others want her to do), and because she is taking responsibility for her own self. For others who have had narcissistic and abusive parents, who experienced neglect and exploitation from those who should have cared for us (and I reckon that’s a good many of us), this is a hard book to read and a hard book to put down. I’m glad I read it and I’m glad I’m done reading it.

13. Beaton, Kate. Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands (2022).

Kate Beaton is well-known and -respected in the graphic novels/comix world. He graphic novel about the time she spent in the Oil Sands in so-called Alberta was much anticipated and received several rewards and high praise from the critics. Those things were well-deserved. This is an excellent meditation on home, belonging, extractive capitalism, ecocide, settler colonialism, heteronormative toxic masculinity, positionality and accountability, all told in a way that makes good use of the graphic novel medium itself. It flows well and is hard to put down once you start into it.

Initially, I was unsure if I wanted to read it. I’ve read enough and watched enough about the oil sands (or tar sands as they’re frequently called) to know about the devastation wrought there. It breaks your heart, fills you with rage and despair. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to feel all of these feelings at this time. But I’m very glad that I decided to read Ducks. Recommended reading.

14. Waldman, Anne. Trickster Feminism (2018).

Longform poetry is not my jam. Ditto for esoteric poetry and poetry that only has a minimal amount of coherence. I reckon Anne Waldman’s poetry is better intended to be experienced by an audience while she performs it, than read by a reader like me. Because, for a reader like me, this is a nope.

15. Ibn `Arabi, Muhyiddin. The Translator of Desire: Poems (Trans. By Michael Sells, 2021).

Usually, poetry that was written hundreds of years ago does not affect me overly much. Also usually, collections of love poems leave me feeling like I should be feeling more than I’m actually feeling. However, in this instance I rather enjoyed the love poems penned by this Andalusian poet. The simplicity of the writing, the recurrence of a few set themes, motifs, and images, had both a saddening and calming affect on me.

16-18. De Mattos Frisvold, Nicholaj. Pomba Gira and the Quimbanda of Mbùmba Nzila (2011); Maggi, Humberto. Queen of the Seven Crossroads (2020); and Maggi, Humberto and Verónica Rivas. Maria de Padilla: Queen of the Souls (2015).

I’m not going to comment on these books at this time. If you’re reading them, they’re for you.

Movies

1. Baumbach, Noah. White Noise (2022).

It has often been said that the novels of Don DeLillo, one of the most influential figures in postmodern American literature, are impossible to translate into film. Of the novels I have read by him (White Noise, Libra, and Underworld), White Noise remains my favourite. It’s flow, the narrative voice, the way it weaves various elements together, creates a remarkable work. It is deceptively simple. “I could write that way,” the inspired reader thinks… until, in fact, they try to write that way and realize that the seemingly effortless affect DeLillo exhibits, is an illusion created by a true master of the craft of writing. So, yes, hard to translate into film. But this doesn’t stop Noah Baumbach (and his frequently collaborator, Greta Gerwig, amongst others) from trying to make a movie out of White Noise. They give it a valiant effort and have enough talent to produce something decent. But, alas, my viewing of the film was ruined by my appreciation of the book.

2. Jusu, Nikyatu. The Nanny (2022).

Sometimes, at great personal cost, parents do what they feel they must do in order to provide what they imagine is the best possible life for their children. And sometimes, through no fault of their own, the decisions those parents make end up having tragic consequences for their children. All of this on display in Nikyatu Jusu’s film about a Senegalese nanny who looks after the daughter of a rich White family in New York City, while hoping to bring her own son over to live with her. Of course, while Aisha (the nanny) is not to blame for the tragedy that unfolds—it has far more to do with border imperialism and racialized capitalism (which Jusu does a fine job of demonstrating in the interactions between Aisha and the parents of the child she nannies)—she does not experience herself as blameless (nor, for that matter, can her son understand that her mother is not to blame). That said, I do wish Jusu had spent more time diving into the subtle exploitation, racism, and violence of wealthy Liberals and White feminists, as well as the traumas of forced migrations from nations that are dispossessed by “the West” (I felt like this was the real horror demonstrated in the film), and less time moving towards more traditional horror themes. Regardless, I still enjoyed the movie.

3. Coote, Suzanne and Matt Angel. The Wrath of Becky (2023).

When the sequel to a horror movie about a teenage girl who kills neo-Nazis (Becky [2020]), gets higher praise than the original, I figured it might be worth checking out for some mindless fun. Given the theme of the sequel—it revolves around Becky now killing members of a group very obviously modeled off of the real-life “Proud Boys”—it seemed potentially cathartic. Unfortunately, it didn’t live up to me minimal expectations. Poor directing, poor acting, poor plot development… it actually wasn’t nearly as fun as it could have been. Oh well.

4. Loach, Ken. Sorry We Missed You (2019).

Ken Loach is, undoubtedly, the film-maker who understands, represents, loves, despairs, and rages with, everyday working people. I, Daniel Blake (2016), was a near perfect presentation of the creeping impoverishment that accompanies ageing within the increasing capillary spread of neoliberalism and the ways in which the non-profit industrial complex is designed not so much to care as to engage in the economics of extractive abandonment in relation to the dispossessed. In Sorry We Missed You (2019), Loach turns his gaze to the “gig economy” and the devastation precarious labour inflicts upon the families of increasingly exploited workers. Again, it’s a top-notch analysis that shows more than tells which, I think, is essential when trying to engage viewers on these things. Highly recommended.

5. De Swaef, Emma, et al. The House (2022).

The House tells three short stories (in not entirely overlapping worlds) about what goes on in the titular house. A multitude of creative directors are involved and the stop-motion animation is fantastic. Each tale is haunting and humourous. The feelings they provoke, combined with the mastery of their distinctive style, reminded me of the graphic novels of Emily Carroll or the short stories of Carmen Maria Machado. Very fun and very well-done.

6. Silveira, Anita Rocha de. Medusa (2021).

By the end of this movie, I was laughing out loud and cheering what was happening on the screen. What a fun film! What an excellent takedown of Evangelical Christianity and the rapacious and toxic masculinity that goes with it. And it is written and directed by a woman, stars women, and centres women not merely as victims but as complex characters moving from oppression—and active participants in oppressing others—to mutual liberation. Highly recommended. And if you watch it, tell me how it makes you feel and what you think about it!

7. Khabensky, Konstantin. Sobibor (2018).

In 1943, the Jews at Sobibor, a Nazi-run extermination camp in Poland, revolted. In this revolt, 11 SS-Officers were killed and more than 300 prisoners escaped. Khabensky’s 2018 Russian film attempts to tell this story but, in my opinion, does not do such a very good job of it. In many ways, it felt like an updated version of The Great Escape (1963) with a bit of Schindler’s List (1993) thrown in (both being highly problematical presentations of war, life in the Lagers, and genocide). Purportedly a story of Jewish courage and resistance, it ends up feeding into stereotypes and transforming torture and the mass production of death into art. I’m a bit of a Russophile when it comes to cinema, but I don’t recommend this one.

Documentaries

1. Fleit, Rachel. Bama Rush (2023).

So-called “Greek life” (i.e., frats and sororities) plays a prominent role in a lot of documentaries about both bullying and sexual violence on university campuses in the United States. The partying and recruitment processes that occur during “rush week” (when new members are admitted at the beginning of the school year) are shrouded in secrecy (often due to ritualistic violence, systemic racism, and epidemic levels of sexual assault). The University of Alabama is reputed to have the wildest parties and most extravagant, expensive, and over-the-top rush week (it has gone viral a few times on social media) and so Rachel Fleit focuses her attention here. Well, as much as one can say that she focuses her attention on anything. Because the great flaw of this documentary is that while it touches on all kinds of things related to Greek life, rush week, racism, sexual violence, elite (i.e. very rich people) capture of the student body, how the process is experienced by some young ladies going through it, how the process is experienced by the director herself, as a women who has had alopecia since she was a young girl, it never seems to find its footing anywhere and never really dives too deeply into any one thing. Which is too bad. This documentary works as a mild form of entertainment but not as much else.

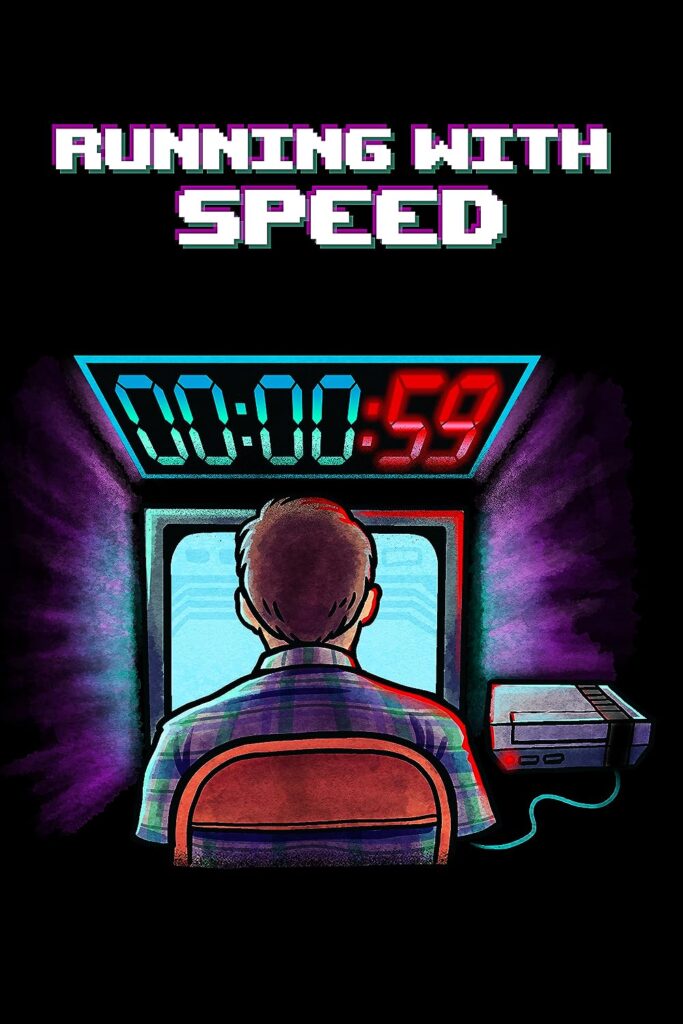

2. Lope, Patrick and Nicholas Mross. Running with Speed (2023).

My son enjoys gaming and enjoys watching various youtube channels that discuss various elements of gaming and one of the topics he likes to learn about is speed running. This is when gamers complete games in the fastest possible way (often looking for glitches in the game itself that allow them to hack the game in some way, although various forms of speed running have different sets of rules as to what you can or cannot do). So, I watched this documentary with my son. We had a good time together. That’s about it.